Paranoia, Parapolitics, and the Psychogeography of Southern California in Cinema

Here we are, at the end of the world.

How else can you describe the southwest corner of the western most coast of the hemorrhaging empire that is the United States of America?

Colonial violence brought us here, to the bleeding edge of the California coast, and here we can witness the most hyperbolic and surreal examples of the imperial boomerang coming back to the imperial core.

As the post-war, post-Cold War, post-9/11, and post-COVID epochs have continued to drive both our consumption and our labor to virtual, fictionalized, and heterotopic spaces or sites, I want to highlight these specific examples of the moving image which can be understood as challenges to what can be considered to be a neurotic relationship to sociopolitical realities, paranoia, and parapolitics.

First, for a quick and dirty definition of parapolitics.

Parapolitics is/are the strategies, programs, or forces which act parallel to the ‘official’ political processes.

They are often meant to disguise, obfuscate, and misinform the realm of the governed (the polis or socius) by those with power that are more often than not, not elected. Parapolitical forces are inherently anti-democratic, esoteric, and often openly embrace the methods of fascistic power; be that aesthetically, sociopolitically, or intellectually.

Important for this short work is not only the recognition of parapolitics and the continually strengthened grip it retains on our understanding of the traditional categories of the political, social, and the aesthetic, but crucially how these paranoiac recognitions of such orders of power dynamics are both increasingly defined by visual culture (movies in this case), and how some of these movies which cover said parapolitical/schizophrenic/paranoiac films are set right here in our backyard, at the end of the world.

Los Angeles.

Understanding the rabbithole of conspiratorial power and control which are at work all around us, and continually permeate and operate with and at various levels of opacity have - as a byproduct - intended this as a goal. This often manifests in clandestine pockets of both those who are; on the one hand enforcing said powers, and on the other are combatting it. Then, of course, there are those who are stuck in between and in the process of uncovering said parapolitical realities. Sometimes the best examples of this attempted uncovering or exposure to these realities come from the very heart of the virtual postmodern capital of the world here in Los Angeles.

This attempt at exposure of the deeper or obscure/esoteric/occult understandings of power brings us to our first example of parapolitical paranoia: the Coen Brothers’ “The Big Lebowski”,and while this will act in no way as a movie review(s), nor coming from a movie critic, I want to highlight a handful of themes which are central to the plot(s) which as you will see will become common threads throughout the films we will continue to discuss.

Just to break down the most basic parapolitical facts of the film. First, Jeff Bridges character “the Dude” is a stoner and heavy drinker. In fact the near constant indulgence in substances is a hallmark of the movie itself, and will be a recurring theme in the films discussed following. Second, “German nihilists”, (which I argue is a very simple metaphor for fascism and fascists) provide the most odd or uncanny antagonists in the film, and which truly makes any understanding of any line between protagonist and antagonist as blurry as possible. Third, is the connection between the sex industry and clandestine power. Treehorn, the antagonist pornographer socialite is portrayed to be living in the Sheats-Goldstein home in Beverly Crest, and representative of much of the underbelly (be it high class, or low) of our collective Los Angeles.

Now, the Big Lebowski is a surreal and hilarious trip, was received coldly from critics on release in 1998, but which has since been recognized as a cult classic, and one which crucially to this discussion introduces many of the same themes which will resurface, often in much darker forms.

If we were to look at literary examples of parapolitical paranoia in Southern California and the southwestern United States, the list would go on and on. Sinclair’s “Oil!”, much of Hunter S Thompson’s entire bibliography involving Hells Angels, nazis, drugs, corruption, etc. But if there is one author who embodies this type of paranoia which is emblematic of the psychogeographical space, it would be the clandestine author par-excellance Thomas Pynchon and his prophetic and esoteric descriptions of Southern California. While I still patiently await for a cinematic adaption of the “Crying Lot of 49”… one of the best examples of this kind of parapolitcality in film can be found in Thomas Paul Anderson’s 2014 adaptation of Pynchion’s “Inherent Vice”.

While the ‘literary petit-bourgeois’ often talk down on the novel for being Pynchon’s “most approachable” and thus his least interesting or successful, the challenge Anderson undertook (and I argue succeeded at) in taking an inherently paranoiac, schizophrenic, and parapolitical referential text still proves itself to be a pinnacle of the genre of the paranoiac parapolitical.

But even here we can see obvious parallels between the Big Lebowski and Inherent Vice.

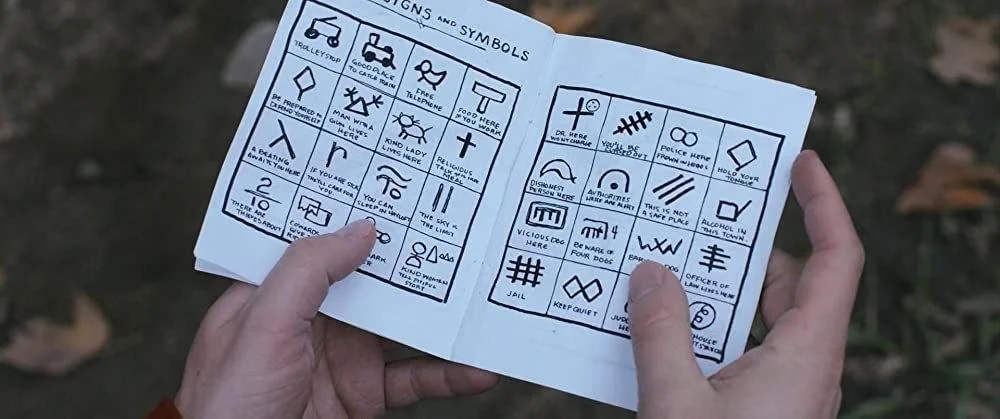

A stoner private investigator protagonist, Doc, played by Joaquin Phoenix, haphazardly stumbles his way through Los Angeles in an initial attempt to find a former lover, which lead him into the underbelly of drug dealers, property conglomerates, freaky cops, and a recognition of the evershifting - or rather ever parapolitically programmed - psychogeographic landscape of Los Angeles.

The differences between the two - in typical Pynchonian fashion - are in terms of intensity. A perfect example of this is seen in the antagonists themselves. Rather than ‘monotone German nihilists’ riding BMW K1100 LT bikes, we are faced with intimidating swastika tattooed Nazi bikers riding Harley Davidsons. Rather than high-brow pornographers, we are faced with a heroin cartel being run by a mysterious cult. And yet, interestingly enough at the core of each ‘narrative’, we find a power center emblematic of parapolitics, be it the ‘other Lebowski’, or the ‘Golden Fang’, in each movie respectively. At the surreal and parapolitical bottom of each of the films, we find our protagonists running into a source of power which is either too rich to be bothered, or too esoteric, surreal, and cultish to be ever truly exposed.

In even more contemporary setting, or at least depictions of Los Angeles as such, can be found in 2018’s “Under the Silver Lake”, in which a mixture of peak A24 drama and Pynchonian symbolism leads the narrative through the drug-induced subterranean topography of the city. Mixing what would come to be well-known as the A24 style of narrative and cinematography, and a wealthy cult not too dissimilar to Kubrick’s “Eyes Wide Shut”, “Under the Silver Lake” synthesizes the surreal humor of “the Big Labowski” with the neo-noir darkness of “Inherent Vice”. The tunnels and sealed graves of 2018 in some ways come to replace or imitate the odd and suspicious appearance of the Golden Fang tower building set 40 years prior.

A common theme between these films is a denial of a true answer to any of the problems presented. Southern California seemingly swallows any potential for that whole, and spits back out fragments of the parapolitical power structures which live both in the tunnels and towers of the physical landscape.

In fact, the punctum of two blockbuster films hinge directly on this lack of an answer, a ‘parapolitical cliff-hanger’, per say could be observed in David Fincher’s 1995 “Se7en”, and Quentin Tarantino’s 1994 “Pulp Fiction”.

While obviously both films also maintain the clandestine, violent, and illegal activities which also are uncovered or detailed in the prior mentioned films, there are certain specific set pieces which can be understood as material embodiment of the paranoiac parapolitical.

In “Se7en”, while the setting is not explicitly told to be Los Angeles, but the film being very obviously shot in LA and in the southwestern landscape outside of the city ends with the infamous question of “Whats in the box?”. A question in which the answer is assumed, but never truly revealed to the viewer.

In “Pulp Fiction” the plot or narrative itself can be read as schizophrenic, hopping from one cast to another, only occasionally and often violently intersecting, but also hinges on the question of: what is in the briefcase? In both cases the punctum of the box and briefcase are never truly revealed to the viewer, there is a maintained level of subversion from what we want to confirm to be truth.

What should we make of all this?

I’m not sure... and it is not as though these are the only examples of the Los Angeles paranoiac-parapolitical; Chinatown, True Detective Season 2, Falling Down, Training Day, etc. all could have been easily plugged into this dialogue for a further diagnosis of this phenomenon.

But recognition of us being here… present at the end of the world which is Los Angeles, I only argue that we must understand how our individual and collective sociopoliticality has shifted towards the virtual, the image, the screen… and while previously understood categories of the political and the social continue to become blurred and conflated, it is perhaps necessary to look towards the pieces of media which understand this parapolitical and paranoiac shift with an attempt to find lines of flight and methods of militancy against said subversive and obfuscated methods of control… But in the end I guess that's “just like, uh, my opinion, man…”.